Mass Graves of Francoism. Archaeology, Anthropology and Memory

Andrea Moreno Martín

Antonio Vizcaíno Estevan

Miguel Mezquida Fernández

Xurxo M. Ayán Vila

2023

Museu de Prehistòria de València , 212 p.

[page-n-1]

[page-n-2]

[page-n-3]

[page-n-4]

MASS

GRAVES OF

FRANCOISM

ARCHAEOLOGY,

ANTHROPOLOGY AND MEMORY

[page-n-5]

MASS GRAVES OF FRANCOISM.

ARCHAEOLOGY, ANTHROPOLOGY AND MEMORY

De julio 2023 a abril 2024

DIPUTACIÓ DE VALÈNCIA

President

Antoni Francesc Gaspar Ramos

Delegate for the Area of Culture

Xavier Rius i Torres

Delegate for Historical Memory

Ramiro Rivera Gracia

DELEGATION FOR HISTORICAL MEMORY

Head of the Delegation for Historical Memory

Francisco Sanchis Moreno

Specialist in Historical Memory

Eva García Barambio

Picture archive

María Jesús Blasco Sales

VALENCIA PREHISTORY MUSEUM / ETNO

Director of the Valencia Prehistory Museum

María Jesús de Pedro Michó

Head of the Unit of Dissemination, Education and

Exhibitions at the Valencia Prehistory Museum

Santiago Grau Gadea

Director of ETNO. Valencia Ethnology Museum

Joan Seguí Seguí

Exhibition Production Unit, ETNO.

Valencia Ethnology Museum

Jose María Candela Guillén and Tono Herrero Giménez

Administrative management

Ana Beltrán Olmos and Manolo Bayona Gimeno

Image design for the project “The mass graves of Francoism.

Archaeology, Anthropology and Memory”

La Mina Estudio

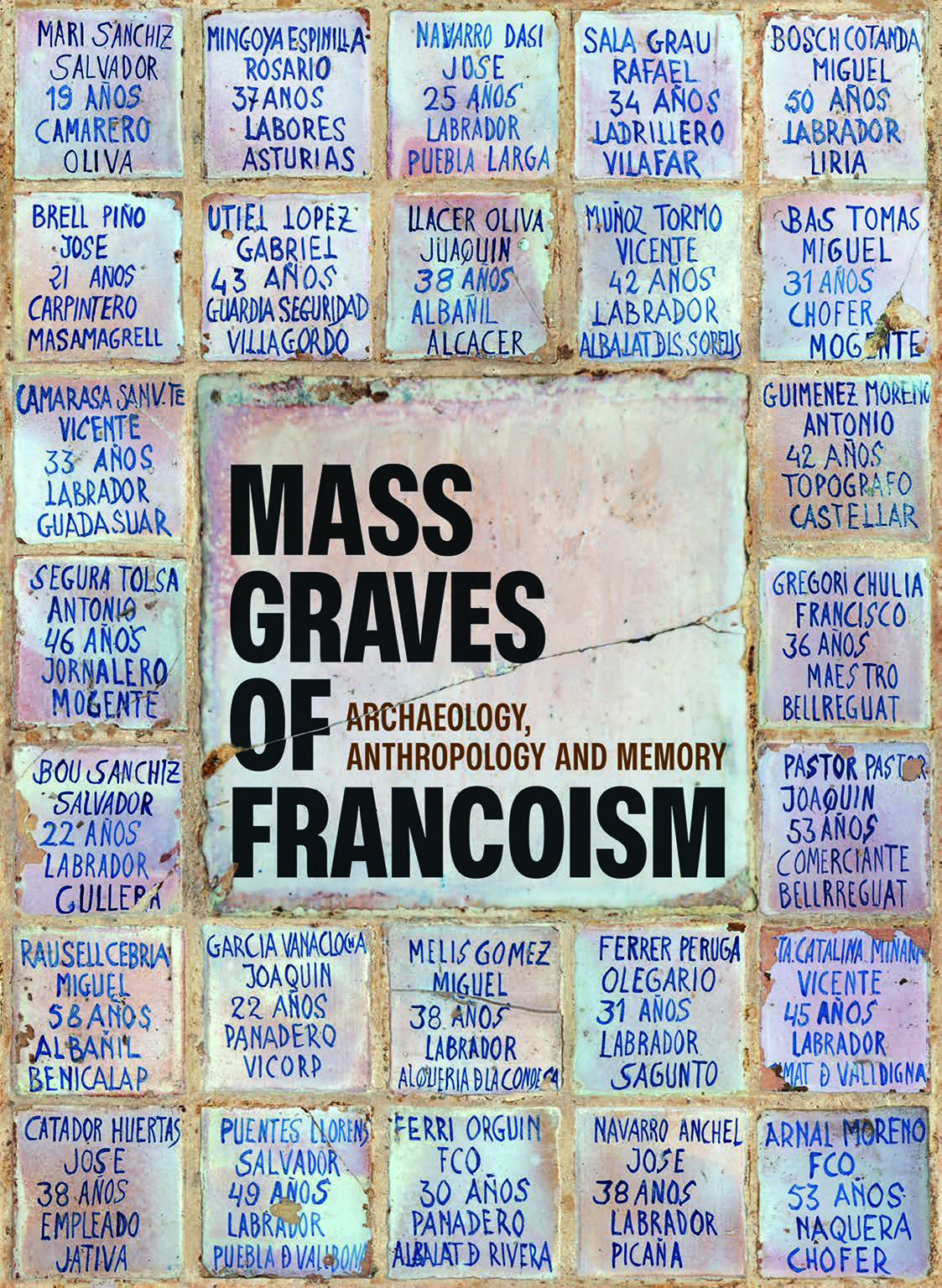

Based on the art work of Dionisio Vacas, Grave 126, Paterna

Cemetery

Photograph of the art work

Chisco Ferrer

Restoration of materials

Restoration laboratory of the Valencia Prehistory Museum:

Trinidad Pasíes, Ramón Canal Roca and Janire Múgica

Mestanza. Con la colaboración del Institut Universitari

de Restauració del Patrimoni - Universitat Politécnica

de València: Mª Teresa Doménech Carbó, Jose Antonio

Madrid García, Pilar Bosch Roig, Sofía Vicente Palomino,

Mª Antonia Zalbidea Muñoz and del Departamento de

Química Analítica - Universitat de València: Antonio

Doménech Carbó

Restoration laboratory, ETNO: Isabel Álvarez Pérez and

Gemma Candel Rodríguez. Con la colaboración de: IVCR+i

Institut Valencià de Conservació, Restauració i Investigació:

Gemma Contreras Zamorano, Mercè Fernández and María

José Cordón

Restoration of textile materials: Carolina Mai Cervoraz,

Núria Gil Ortuño, Carlos Milla Mínguez and Albert Costa

Ramon. Control biológico y conservación preventiva:

l’Institut Universitari de Restauració del Patrimoni Universitat Politècnica de València: Pilar Bosch Roig

Programme of complementary activities

Begonya Soler Mayor, Yolanda Fons Grau, Tono Vizcaíno

Estevan and Andrea Moreno Martín, Francesc Cabañés

Martínez, Ana Sebastián Alberola, Rosa Martí Pérez,

Ivana Puig Núñez, Amparo Pons Cortell, Albert Costa

Ramon, Isabel Gadea Peiró, Mª José García Hernandorena,

Francisco Sanchis Moreno, Eva García Barambio

Production and installation of exterior graphics

Simbols

Printing of the poster and the programme of activities

Imprenta Diputació de València

PUBLICATION

Authors

Eloy Ariza Jiménez, Xurxo M. Ayán Vila, Zira Box Varela,

Isabel Gadea Peiró, María José García Hernandorena,

Baltasar Garzón Real, Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri, Aitzpea

Leizaola, María Laura Martín-Chiappe, Miguel Mezquida

Fernández, Andrea Moreno Martín, Carmen Pérez

González, Francisco Sanchis Moreno, Queralt Solé i Barjau,

Mauricio Valiente Ots, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan

Scientific coordination

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

María José García Hernandorena, Isabel Gadea Peiró,

Francisco Sanchis Moreno

Technical coordination

Eva Ferraz García

Design and layout

La Mina Estudio

Translation and correction in Valencian and Spanish

Joaquín Abarca Pérez and Sarrià Masià. Serveis Lingüístics

Images and photographs

Eloy Ariza Jiménez-Asociación Científica

ArqueoAntro, Albert Costa Ramon. Colección

Memoria Democrática L’ETNO, Isabel Gadea Peiró,

María José García Hernadorena, Xurxo M. Ayán Vila,

[page-n-6]

Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri, Sociedad de Ciencias Aranzadi,

Aitzpea Leizaola, María Laura Martín-Chiappe, Matías

Alonso, Bruno Rascão, Colección particular València,

Colección Familia Roig Tortosa, Familia Pastor, Familia

Chofre, Familia Gómez, Familia Coscollà, Familia Peiró,

Familia Pomares, Familia Gomar, Familia Llopis, Familia

Morató, Familia Alemany, Familia Miguel Cano and María

Navarrete, Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte - Centro

Documental de la Memoria Histórica, Agencia EFE,

Biblioteca Nacional de España.

© de los textos: la autoría

© de las imágenes: la autoría, archivos y colecciones

© de la presente edición: Diputació de València, 2023

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A la Plataforma de Asociaciones de Familiares de Víctimas

del Franquismo de las Fosas Comunes de Paterna, a las

Asociaciones de Familiares de las fosas 21, 22, 81-82, 9192, 94, 95, 96, 100, 111, 112, 114, 115, 120, 126, 127, 128, los

nichos 43-44 and la Agrupación de familiares de Víctimas

del Franquismo de las Fosas Comunes del Cuadro II del

Cementerio Municipal de Paterna.

A Enrique Abad Aparicio, Llorenç Alapont, Dolores

Albuixech Domingo, Montserrat Alemany, Vicente Alemany

Morell, Magdalena Almiñana Solanes, Matías Alonso,

Pedro Luís Alonso, Mercedes and Jaime Amorós Gómez,

Maruja Badia, Amparo Belmonte Orts, Pepa Bonet, José

Calafat Ché, Paz Calduch, Lola Celda Lluesma, Rosana

Copoví, Amparo Cortelles Raga, Rosa Coscollá, Fernando

Cotino, Celia Chofre Rico,Rocío Díaz, Francisco De

Paula Rozalén Martínez, Mireia Doménech Alemany,

Aure Escrivá Ferrer, Joaquín Esparza Morell, Fina Ferre,

Nati Ferrero, María Frasquet, Palmira Flores Carreres,

Palmira Ros, Sara Ros and Geles Porta, Vicent Gabarda

Cebellán, Daniel Galán Valero, Iker García, Vicent García

Devís, José García Martínez, María Gómez, Salvador

Gomar Pons, Carmen Gómez Sales, Carlos and Amparo

Gregori Berenguer, Tina Guillem Cuesta, José Guirao

Giner, Juan Guirao Ortuño, Josefina Guzmán Navarro,

Vicenta Juan, Amèlia Hernández Monzó, Eva Mª Ibáñez

Cano, Mª Rosa Iborra Gimeno, Charo Laporta Pastor,

Gloria Lacruz León, José Ignacio Lorenzo, Concepción

Llin Garcia, Pilar Lloris Macián, Mercedes Llopis Escrivá,

Paqui Llopis, Teresa Llopis Guixot, Ernesto Manzanedo

Llorente, Aurora Máñez, Matilde Martí Avi, Sonia

Martínez, María Asunción Martínez, Carolina Martínez

Murcia, José Ramón Melodio, Rafael Micó, Silvia Mirasol

Fortea, Laura Mollá, Paco Monzó y Toni Monzó Ferrandis,

Josep Joan Moral Armengou, Maria Morató Torres, María

Morió Gómez, José Vicente Muñiz y Helena Aparicio,

María Navarro Giménez, Miguel Navarro, Óskar Navarro

Pechuán, Mª Ángeles Navarro Perucho, Vicente Olcina

Ferrándiz, Roser Orero, Eduardo Ortuño Cuallado, David

Pastor, Josefa Peiró, Pepita Peiró, Vicenta Pérez Martínez,

Conchín Pia Navarro, Carmen Picó Monzó, Juan Luis

Pomares Almiñana, Eduardo Ramos, Jordi Ramos, Raquel

Ripoll Giménez, Verónica Roig Llorens, María José y Charo

Romero Ortí, Andrea Rubio, Benjamín Ruiz Martí, Juan

José Ruíz, Carmen Sanchis Bauset, Mercedes Sanchis

Bonora, Mª Carmen Sancho Albiach, Pablo Sedeño Pacios,

Núria Serentill y Julio Morellà, Laura Simón, Saro Soriano

Llin, Pilar Taberner Balaguer, Laura Talens, Silvia Talens,

Sergi Tarín Galán, Dionisio Vacas Cosmo, Progreso Vañó

Puerto, Fernando Vegas.

A ARFO-Asociación de Represaliados/das por el

Franquismo de Oliva, Ateneo Republicano de Paterna,

Museo de Cerámica de Paterna, Asociación Científica

ArqueoAntro, ATICS, PaleoLab, Museu Virtual de Quart de

Poblet, Cementerio Municipal de Paterna.

IN MEMORY OF ALL THE VICTIMS OF THE

FRANCOIST REPRESSION

[page-n-7]

VALENCIA PREHISTORY MUSEUM

Director

María Jesús de Pedro Michó

Head of the Unit of Dissemination, Education and Exhibitions

Santiago Grau Gadea

Exhibition: The Archaeology of Memory. The mass graves

of Paterna

Exhibition curators

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan, Eloy Ariza

Jiménez and Miguel Mezquida Fernández

Coordination

Eva Ferraz García and Santiago Grau Gadea

Museum project

Rosa Bou Soler and Kumi Furió Yamano. LimoEstudio

Scientific advisers

Associación Científica ArqueoAntro

Display coordination

Rosa Bou Soler, Kumi Furió Yamano, Eva Ferraz García, Laura

Fortea Cervera e Isabel Carbó Dolz

Registration and presentation of exhibits

Begonya Soler Mayor and Ramón Canal Roca

Teaching programme

Arantxa Jansen, Laura Fortea Cervera and Eva Ripollés Adelantado

Dissemination and social media

Begonya Soler Mayor, Lucrecia Centelles Fullana, Vanessa

Extrem Medrano and Francisco Pavón Tudela

Reporting and news

Gala Font de Mora Martí

Exhibition image design

Rosa Bou Soler and Kumi Furió Yamano. LimoEstudio

Translation and correction of display texts in Valencian and

Spanish

Sarrià Masià. Serveis Lingüístics

Translation of display texts into English

Michael Maudsley

Translation of display texts into Italian

Centro G. Leopardi

Translation of display texts into French

Christine Comiti

Families and institutions that loaned exhumed items

Colección Memoria Democrática - L’ETNO and las

asociaciones de familiares de las fosas 21, 22, 81-82, 91-92, 94,

96, 100, 111, 112, 114, 115, 120, 126, 128, los nichos 43-44 y la

fosa 2 del segundo cuadrante.

Colecciones particulares de Enrique Abad Lahoz, Manuel Amorós

Aracil y María Sánchez Gomariz, Manuel Bauset Tamarit,

Juan Bautista Solanes, Miguel Cano and María Navarrete,

Daniel Galán Valero, Regino García Culebras, Manuel Baltasar

Hernández Sáez and Gracia Espí Roca, Pepita Iborra, Lacruz,

Salvador Lloris Épila, Manuel Lluesma Masia, Gregori Migoya,

Vicente Muñiz Campos, Mª Ángeles Navarro Perucho, José

Orts Alberto and Asunción Granell Martí, José Peiró Calabuig,

Conchín Pía Navarro, César Sancho de la Pasión, Carlos Talens

and de las familias Carreres Duato, Ché Soler, Gómez Sales,

Monzó Cruz, Morell Pérez, Murcia-Ródenas, Ortí-Fita, Picó

Monzó, Roig Tortosa, Taberner Giner and Vañó Puerto.

Individuals and institutions that loaned

documents and photographs

Archivo ABC; Archivo Vicaría de la Solidaridad. Museo de la

Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, Chile; Arxiu General i

Fotogràfic de la Diputació de València; Auschwitz- Birkenau

Memorial; Agencia EFE; Biblioteca Historicomèdica «Vicent

Peset Llorca» - Universitat de València; Biblioteca Nacional de

España; Biblioteca Valenciana Nicolau Primitiu. Fons Finezas;

Buchenwald Memorial Collection; Col·lecció particular Matías

Alonso; Colección particular Rosario Martínez Bernal; CRAI

Biblioteca Pavelló de la República - Universitat de Barcelona;

Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site; Fundación

Sancho el Sabio Fundazioa (Vitoria-Gasteiz). Fondo Sociedad

de Amigos de Laguardia; Fundación Biblioteca Manuel

Ruiz Luque. FBMRL; GrupoPaleolab® and UNDERBOX;

Mauthausen Memorial; Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte.

Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica; Ministerio de

Defensa. Archivo General e Histórico de Defensa; Museo Sitio

de Memoria ESMA, Argentina; Museu Virtual de Quart de

Poblet; US National Archives at College Park. National Archives

and Records Administration.

Photographers

Eloy Ariza Jiménez, Paco Grau, Paloma Brinkmann, J. Cabrelles

Sigüenza, Santi Donaire, David Fernández, Maysun Visual

Artist, Bernhard Mühleder, Ahmed Jallanzo, Hermes Pato,

Joaquín Sanchis Serrano «Finezas», Pawel Sawicki and Nathalie

Valanchon.

© Stefan Müller-Naumann, Peter Hansen, Gervasio Sánchez,

Vicente Ballester, Wila, VEGAP. València. 2023

Illustrators

Flavita Banana, Manel Fontdevila, Eneko las Heras Leizaola,

Gema López «Kuroneko», José López «Lope», Ana Penyas,

Bernardo Vergara and Frente Viñetista. Asociación de

humoristas gráficos.

© Andrés Rábago «El Roto», VEGAP. València. 2023

Audiovisual resources

Genocidios y arqueología forense (audiovisual)

Script: Eloy Ariza Jiménez, Andrea Moreno Martín

and Tono Vizcaíno Estevan

Editing: Alicia Alcantud and Pablo Vigil

Paterna, la memoria de la represión y de los crímenes de

postguerra (audiovisual)

Script: Eloy Ariza Jiménez, Andrea Moreno Martín

and Tono Vizcaíno Estevan

Illustrations: Gema López «Kuroneko»

Photography and video: Eloy Ariza Jiménez

Editing: Alicia Alcantud and Pablo Vigil

Los sonidos de una exhumación (paisaje sonoro)

Script: Eloy Ariza Jiménez, Andrea Moreno Martín

and Tono Vizcaíno Estevan

[page-n-8]

Recordings: Eloy Ariza Jiménez

Editing: Marcos Bodi

Translation of display texts into English

Robin Loxley

Las voces de las familias (audio)

Script and editing: Santi Donaire

Families and institutions that loaned exhumed items

Colección Memoria Democrática - L’ETNO, Familia de Juan

Ferrer Vázquez, Familia de Miguel Galán Domingo, Familia

de Salvador Gomar Noguera, Familia de Vicente Gómez Marí,

Familia de Blas Llopis Sendra, Familia de Salvador Llopis

Sendra, Familia de Vicente Martí Ruiz, Familia de Vicente Mollá

Pascual, Familia de José Morató Sendra, Familia de José Orts

Alberto, Familia Peiró Roger, Familia de Juan Luis Pomares

Bernabeu, Familia de Federico Rico Cabrera, Familia de Germán

Sanz Esteve, Familia de Basiliso Serrano Valero, Familia de

Mariana Torres Esquer, Familia de Vicente Guna Carbonell,

Familia de Joaquín Revert Gilabert, Familia de Daniel Simó

Biosca, Familia de Luis Ocaña Navarro, Familia de Vicente Mollá

Galiana.

Resiliencia al olvido (motion graphics)

Pieza artística: Guillem Casasús Xercavins

and Gerard Mallandrich Miret

Motion: Àlex Palazzi Corella

Editing: Joan Campà San José

Production and installation

Rótulos Gallego & Burns S.L.

Carpintería paramentos: Sergio Carrero Melián

Pintura paramentos: Sebastián López

Suelo técnico: Pinazo Decoraciones

Framing

Marc-Imatge

Transport

Tti International Art Services

Image and sound

Sonoidea

Insurance

Allianz

Organization and production

Diputació de València - Museu de Prehistòria de València

ETNO-VALENCIA ETHNOLOGY MUSEUM

Director

Joan Seguí Seguí

Exhibition Production Unit

Jose María Candela Guillén and Tono Herrero Giménez

Exhibition: 2238 Paterna. A place of perpetration

and memory

Exhibition curators

Albert Costa Ramon, Isabel Gadea Peiró and María José García

Hernandorena

Museographic project

Estudio Eusebio López

Display coordination

Jose María Candela Guillén, Albert Costa Ramon and Tono

Herrero Giménez

Teaching programme

Sarah Juchnowicz Perlin and Sílvia Prades Moliner (Exdukere S.L)

Dissemination and social media

Francesc Cabañés Martínez, Ana Sebastián Alberola, Rosa Martí

Pérez, Ivana Puig Núñez, Francisco Alba Ros, Sandra Sancho Ruiz

Image design

Estudio Eusebio López

Translation and correction of display texts in Valencian

and Spanish

Jose María Candela Guillén and Carles Penya-roja Martínez

Audiovisuals

Mujeres Rapadas

Script: Isabel Gadea and Peiró, Mª José García Hernandorena

Photography: Archivo Art al Quadrat, Archivo Pura Peiró

Voice: Teresa Llopis

Editing: Pau Monteagudo Aguilar

Homenajes políticos

Photography and video: Archivo Pep Pacheco, Archivo Sergi

Tarín and Óskar Navarro

Editing: Pau Monteagudo Aguilar

Primeras exhumaciones científicoforenses

Fragmento vídeo: “Dones de Novembre. Les fosses clandestines

del franquisme”

Script and direction: Óskar Navarro, Sergi Tarín

Photography: Antonio Arnau Iborra, Esther Albert Navarro

Music: Jorge Agut Barreda

Movimiento asociativo y nuevos rituales

Images: Raúl Pérez López

Editing: Pau Monteagudo Aguilar

Creation of sound in the cemetery of Paterna

Edu Comelles Allué

Art work Patio 3

Anaïs Florin, Judith Martínez Estrada

Tiles production

Aacerámicas (Almàssera)

Production and installation

Art i Clar, Sebastián López Valero

Technical support

Collections and Restoration Unit

Jorge Cruz Orozco, Miguel Hernández Oleaque

and Pilar Payá Ferrando

Insurance

Allianz

Organization and production

Diputació de València – L’ETNO

[page-n-9]

ARCHAEOLOGY

17

35

Beyond exhumation:

Building Memory

through Archaeology and

Museums

The archaeology of

memory: the application

of forensic archaeology to

the graves of the Civil War

and the postwar period

Andrea Moreno Martín,

Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez

& Miguel Mezquida Fernández

Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri

53

69

The forgotten bodies

of the war

This archaeology will be

the tomb of fascism, or it

will be nothing. The role of

community archaeology in

uncovering the common

graves of Francoism

Queralt Solé i Barjau

Xurxo M. Ayán Vila

ANTHROPOLOGY

91

113

Where does

memory live?

Objects and memories:

the material dimension

of the mass graves

Maria-José García Hernandorena

& Isabel Gadea i Peiró

Zira Box Varela

[page-n-10]

127

145

The past, present and

future of the objects in the

mass graves

A look at Paterna to

revisit the contemporary

exhumation process:

possibilities and tensions

in the fight for memory(ies)

Aitzpea Leizaola

María Laura Martín-Chiappe

DEMOCRATIC MEMORY

165

175

Graves and

Democratic Memory

The right to truth with

regard to the human rights

violations during the

Franco regime

Francisco J. Sanchis Moreno

Mauricio Valiente Ots

189

201

First and foremost, the

victims. Principle of Justice

International Law,

Reparation and

Democratic Memory:

The Case of Spain

Baltasar Garzón Real

Carmen Pérez González

[page-n-11]

[page-n-12]

11

Toni Gaspar

PRESIDENT OF THE PROVINCIAL COUNCIL OF VALENCIA

La historia que no se escribe, prescribe: roughly translated, “the history

that is not recorded is lost”. The sentence in Spanish, with the rhyme

of “escribe, prescribe”, may sound like an advertising jingle, but I think

it actually has a political intent: to reflect the collective principle of a

people, the moral obligation of any free society. Reclaiming what was

concealed, talking about what was silenced, bringing to light what

was suppressed: this, in a nutshell, is historical memory.

The Valencia Provincial Council is proud to have established itself

in recent years as an institutional reference point in the recovery of

memories, testimonies, and remains of people who were hunted

down and shot for their convictions, or simply for not being part of

an undemocratic and repressive regime.

Thirty-five mass graves have been opened, more than 1,200

victims have been exhumed, and more than eight million euros has

been assigned to groups, associations and town halls over the past

six years. The Historical Memory section of the Valencia Provincial

Council has led the way in ensuring that the memory and dignity of

hundreds of families from the region is not forgotten.

The way to silence the ideology of oblivion is to develop projects

and allocate funding for institutions and associations engaged in

the recovery of memory, a mission that is so important for achieving

historical justice for a people.

I would like to thank all the experts from different disciplines

who have helped us in this task of recovering and identifying several

hundreds of the people who disappeared during the Franco dictatorship. Thanks are also due to the staff of the Provincial Council of

Valencia for their dedication to the project. We will continue our task

of recovering this memory, in the absolute conviction that to live life

we must look forward to the future, but that, to understand it, we

must look back to the past.

[page-n-13]

ARCHAE

[page-n-14]

13

EOLOGY

17

Beyond exhumation: Building Memory through

Archaeology and Museums

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan, Eloy Ariza Jiménez

& Miguel Mezquida Fernández

35

The archaeology of memory: the application of forensic

archaeology to the graves of the Civil War and the postwar

period

Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri

53

The forgotten bodies of the war

Queralt Solé i Barjau

69

This archaeology will be the tomb of fascism, or it will be

nothing. The role of community archaeology in uncovering

the common graves of Francoism

Xurxo M. Ayán Vila

[page-n-15]

14

The front and back of a photograph with a farewell message

Vicente Mollá Galiana, Grave 94, Paterna

Mollà Galiana family collection

Photo: Eloy Ariza-ArqueoAntro Scientific Association

[page-n-16]

15

[page-n-17]

Clay dominoes

Salvador Lloris Épila, Grave 21. Paterna

Salvador Lloris Épila family collection

Photo: Eloy Ariza-ArqueoAntro Scientific Association

[page-n-18]

17

Beyond exhumation:

Building Memory through

Archaeology and Museums

Andrea Moreno Martín,

Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez

& Miguel Mezquida Fernández

CURATORIAL TEAM, “THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF MEMORY: THE MASS GRAVES OF PATERNA”

[page-n-19]

18

Beyond exhumation: Building Memory through Archaeology and Museums

“With a steady hand and a clear conscience, I am writing my last words

because in a few hours I will have ceased to exist. I am going to be executed”.

Bautista Vañó Sirera, 15 July 1939.

On 15 July, 1939, Bautista Vañó Sirera was shot in front of the wall

known as the Mur del Terrer, in Paterna. The Franco regime accused

him of rebellion and, after a very short trial in which he had no legal

defence, a military court sentenced him to death. Bautista, born in

1898 in Bocairent and a weaver by trade, was married and the father

of four children. According to his descendants, he was devoted to the

culture and politics of his town and his times: under the pseudonym

of “Progreso” he published articles on social and political issues,

participated in the Sociedad Amanecer and was part of the Bocairent

Popular Executive Committee during the Civil War. His affiliation to

the anarchist groups the CNT and the FAI, and his campaigning for a

fairer, freer world, provided the dictatorship with more than enough

reasons for murdering him.

Bautista’s story is by no means unique. Like him, thousands of

men and women were victims of the structural and systematic violence perpetrated by the Franco regime.1 In Paterna alone, at least

2,237 people2 were shot between 1939 and 1956. Their bodies were

thrown indiscriminately into mass graves, of which there are thousands all over Spain. These murders sought the physical annihilation

of dissent and imposed a State policy to silence and erase the lives of

these people after their deaths, as well as the ideals they defended.

Even today, many of these bodies remain under the ground. The

stark reality is that many of the graves in Spain are still to be located

and exhumed. In fact, some will never be excavated because they

have been destroyed or because other structures have been built on

top of them.

Opening up the earth is a radical act of great symbolism, triggering a complex but necessary process that recovers bodies and

memories, breaks down silences, addresses traumas, and generates

conflicts. Above all, it represents an opportunity to do justice, and to

create a context for individual and collective reparation. In this process, archaeology plays a vital role: it makes it possible to locate, exhume, identify, analyse and interpret the material remains preserved

in the graves in a truly scientific way.3

The archaeological record is made up of the human remains of

the victims, along with the material items they had with them at the

time of their death: from personal objects (clothing, shoes, buttons,

rings, pencils, glasses, medallions), through the material evidence

of the crimes (bullets, cartridges, rope used to tie the hands), to the

1

According to Francisco

Espinosa, the figures

for Spain as a whole are

49,426 victims on the

home front and 140,159

at the hands of the

regime. In the province of

Valencia, Vicent Gabarda

sets the corresponding

figures at 6,415 and

6,386 respectively (2020:

20-21).

2

Although the most

recently published

number is 2,238, we are

trying to corroborate the

identity of a person whose

confirmation as a victim

of the post-war repression remains pending.

In this text we state that

at least 2,237 people

were killed; these are the

people whose names and

surnames and date of execution are known based

on the studies of Vicent

Gabarda (2020).

3

Archaeological practices

require the authorization of the Ministry of

Culture and Heritage

(Law 4/1998 and Decree

107/2017) and are subject

to the regulations set out

in the Democratic Memory Act (Law 14/2017).

Exhumations in Spain

must comply with the

Protocolo de actuación en

exhumaciones de víctimas de

la guerra civil y la dictadura

(Order PRE/2568/2011).

[page-n-20]

19

Glass bottle recorded

next to the body of César

Sancho de la Pasión

during the exhumation

of the mass grave. Photo:

Eloy Ariza-ArqueoAntro

Scientific Association.

Grave 120, Paterna Municipal Cemetery.

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez & Miguel Mezquida Fernández

evidence of the families’ mourning and remembrance (bouquets

of flowers, bottles with handwritten notes, panels bearing the

personal data of the victims as memorials). Apart from the objects

themselves it is important to understand where and how they appear, in order to be able to reconstruct the events and study their

value – symbolic, historical, scientific, social, and personal. Obviously, the scientific interpretation of this material culture must be

based on the context in which it is recovered.

Contrary to what many people may think, archaeology does

not seek to empty out the subsoil in search of objects, but rather,

as a social science, it studies these objects – and their contexts – to

learn more about the people behind them, whether they are from

remote societies or from the recent past. In the specific case of

mass graves, forensics is an important new dimension to add to

the spatial context. Since the aim of these procedures is to locate,

identify and recover people who were victims of human rights

violations, archaeology applies specific protocols and employs

[page-n-21]

20

Beyond exhumation: Building Memory through Archaeology and Museums

interdisciplinary teams of anthropologists, forensic medicine specialists, historians, sociologists, psychologists and lawyers. The

field of forensic archaeology4 intends to shed light on crimes against

humanity, but also to understand the memory-building processes

around these events, to think about the mechanisms for dealing with

the trauma and the management of the conflicts in the family and

in the public sphere, and to encourage the creation of spaces for reflection and debate. Although neither the work of archaeology nor

any other discipline can ensure that crimes of this kind will not be

repeated, at least it offers tools for reflecting on them, with the aim

of raising public awareness of our history.

4

The purpose of archaeology is, therefore, to build and disseminate

knowledge of the past – a past that, we must not forget, begins yesterday – based on a firm engagement with the realities of the present. The

temporal dimension does not limit the practice of archaeology, as this

is a discipline that can be methodologically and epistemologically applied to any chronological context. And when it centres on the recent

past, archaeological research also has access to sources of other kinds

of a crucial importance, such as oral testimonies, historical documentation and personal records.

Families are key actors in

the exhumation processes, and often accompany

technical teams at the site.

Pepita Peiró in front of the

grave where her father lay

(Eloy Ariza-ArqueoAntro

Scientific Association,

Grave 112, Paterna Municipal Cemetery).

Forensic archaeology is

associated with forensic

anthropology, legal medicine and humanitarian

law; thus, it differs from

funerary archaeology,

whose purpose is the

study of death (rituals,

burials, associated remains) in order to analyse

these practices in human

societies from a social and

cultural point of view.

[page-n-22]

21

Pepita Peiró holding the

photo of her family on All

Saints' Day, visiting the

grave of her father, José

Peiró. (Photo: Eloy Ariza,

Grave 112, Paterna Municipal Cemetery).

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez & Miguel Mezquida Fernández

Forensic archaeology is a key part of the study of recent times.

Unfortunately, in Spain it is still in its infancy. Although in the last

two decades some local governments have started to promote public

policies on memory, above all by providing funding for exhumations,

and although historical memory has attained a certain presence in the

media, we are still a long way from achieving an effective commitment

to the triad of “truth, justice and reparation” – at least not at institutional level, because the truth is that the citizens’ associations that

make up the historical memory movement have been claiming these

rights for decades. In fact, the families have never forgotten those that

disappeared, and have been the real drivers of these processes from the

very beginning – some even from the moment of the execution. This

is why, despite the control and repression imposed by the regime, the

transmission of memories in the private sphere has allowed many of

the stories of the victims of reprisals to come down to us today.

[page-n-23]

Beyond exhumation: Building Memory through Archaeology and Museums

Let’s turn back to the story of Bautista Vañó Sirera. A few hours

before the shooting, and fully aware of the crime that was about to

be perpetrated, he wrote his farewell letter. The words are a forceful

expression of his feelings: “in a few hours I will have ceased to exist”.

On that 15 July, 1939, they took his life. But, despite his loss, he never

“ceased to exist”, because Magdalena Puerto Mora, his wife, kept his

memory alive and transmitted it as a legacy to his children, who still

maintain and disseminate it today.

This is how the memory of the people who were shot or who

disappeared has usually been preserved, in the family sphere, where

women have always played the leading role (Moreno, 2018; García

Hernandorena and Gadea Peiró, 2021). Under the dictatorship this

form of resistance – the decision not to forget, and to speak out and

tell others – was a private survival mechanism, and after the return

of democracy it remained an intimate, low-key ritual, the result of

stigmatization and the lack of public recognition. Only recently have

these family stories been listened to attentively, and now they have

become part of the public dimension of memory. This “democratic

memory”, as it has come to be called, is built through the joint participation of institutions, professionals in the field, and civil society

(Baldó, 2021). As we understand it, memory is a right that goes beyond the private sphere and must take on meaning for all citizens.

In this reconceptualization of memory, archaeology has a great

deal to say. Once again avoiding the entrenched stereotypes, archaeology does not just describe the remote or recent past; it also has a place

in the present and future. The knowledge it provides of the past and

its material heritage enable us to rethink and transform our reality

and the reality to come. This is the idea behind currents such as public

archaeology, which proposes a change of perspective: namely, making

the people of the present the true protagonists.

This understanding of archaeology, together with an awareness

of the complexity of exhuming the mass graves of the Franco regime

and the need to enrich the public debate on democratic memory, form

the cornerstone of the exhibition The Archaeology of Memory. The mass

graves of Paterna.

The exhibition is based on the research carried out by the ArqueoAntro Scientific Association in the Municipal Cemetery of

Paterna. For more than a decade, the association has been working

on the recovery and identification of victims of the war and of the

Franco dictatorship in different parts of Spain, especially in the

Valencian region (Díaz-Ramoneda, et al., 2021; Mezquida, et al.

2021; Moreno et al., 2021). In Paterna, between 2017 and 2023,

more than twenty graves have been exhumed. In parallel to the

22

[page-n-24]

23

5

Saponification is a

process induced by a high

level of humidity in the

subsoil that favours the

body’s preservation. It

occurs through a process

of chemical change that

affects the body fat,

which is transformed

through hydrolysis into

a compound similar to

wax or soap. In Paterna,

saponification has been

documented in several

graves, at depths of more

than four metres, and has

allowed the exceptional

preservation of anthropological remains, clothing

and a set of other items

(Moreno et al., 2021).

6

Particular thanks to each

and every one of the

families and associations

that have accompanied us

in this exhibition project

for their enthusiasm and

commitment; for the care

and affection with which

they described their family objects; for the trust

they showed in us in

sharing their most intimate and personal memories, and for allowing us

to tell their stories.

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez & Miguel Mezquida Fernández

field work, ArqueoAntro has brought the project to a wider public

through the publication of articles and the organization of conferences, courses, guided tours and exhibitions. In 2018 ArqueoAntro

collaborated in the exhibition “Prietas las Filas. Daily life and Francoism” in L'Etno, where some of the materials exhumed in the mass

graves of Paterna were exhibited for the first time (Moreno and

Candela, 2018).

With these precedents, the project for the current exhibition

was put forward in late 2019, with a specific aim in mind: to present the material culture exhumed in the graves of the Municipal

Cemetery of Paterna from an archaeological perspective, applying

a comprehensive approach that explains and contextualizes the scientific process of exhumation, and demonstrating the uniqueness

of Paterna in several areas: as a place of memory since the post-war

period; as a site of barbarism and horror, due to the numbers of victims and the use of the cemetery as a mass burial ground; and as an

unusual example of conservation, as some of the remains have been

preserved in an exceptional condition due to a process known as

saponification5.

To meet the multiple challenges posed by the project, it was

decided to form an interdisciplinary curatorial team, comprising

experts in exhumation processes, heritage management and public

memory policies, and museum management. Specialists from the

fields of photojournalism, art and design also took part. Most importantly, in an act of enormous generosity, the families of the victims

have loaned certain objects that they kept at home in memory of their

missing relatives (for example, photographs, letters, personal items)

and allowed the us to display some of the exhumed objects, enveloping them in signficance and affection with their personal stories.

The close relationship between the technical team and the families,

following years working together and meeting at the foot of the grave,

made this joint participation possible. To all the families, once again,

we express our most sincere thanks6.

Given the archaeological nature of the project, the curatorial

team felt that the ideal venue for the exhibition was the Museum

of Prehistory of the Provincial Council of Valencia. The museum is

a reference centre for archaeology in both Valencia and Spain as a

whole, and its geographical proximity to Paterna is another reason

for its choice. The project represented a major challenge for the

museum; there are hardly any precedents of analyses of the role

of archaeology in the construction of the historical memory linked

to the mass graves of the Franco regime, or exhibitions in which

exhumed materials constitute the central theme. This is why it

[page-n-25]

24

Beyond exhumation: Building Memory through Archaeology and Museums

is important to emphasize the museum’s firm support and engagement in the project7.

The launch of the project had three main objectives in mind.

First, the exhibition is a tribute and a public recognition of the victims

of Franco’s repression and their families, and of the groups and individuals who, for decades, have fought for the preservation of their

memory. Second, to highlight the work of the scientific and technical

teams which have exhumed the graves, identified the victims and

recovered their life stories. And, third, to establish a dialogue with

society about the need for public policies of memory, in order to face

the traumas of the past, to raise public awareness of the issue, and to

address the challenges of the future.

The exhibition is structured in five large areas, and takes visitors

on a journey that moves intermittently between the present and the

past. The starting point is the celebration of the role of archaeology in

the study of contemporary world, in particular in the field of conflicts

and traumatic episodes around the world during the 20th and 21st

centuries. First, we situate our case study in the international context

of human rights, and connect it with the principles of forensic archaeology in its role in compiling expert evidence of crimes.

7

The exhibition The

Archaeology of Memory:

The mass graves of Paterna

owes its existence to the

dedication of María Jesús

de Pedro, director of the

Museum of Prehistory,

and Santiago Grau, head

of the Dissemination,

Teaching and Exhibitions

Unit, and the curators

and technical staff: Eva

Ferraz, Begoña Soler,

Ramon Canal, Trinidad

Pasíes and Yanire Múgica.

Their work in the field of

management, restoration

and museography and the

contributions that arose

in the work sessions and

informal conversations

were fundamental for the

success of the project.

[page-n-26]

25

Carolina Martínez, granddaughter of José Manuel

Murcia Martínez (Grave

94, Paterna Municipal

Cemetery) during the

process of transferring

objects for the exhibition. (Photo: Eloy Ariza,

Museum of Prehistory of

Valencia).

Rendering of the exhibition “The archaeology

of memory: the mass

graves of Paterna” at the

Museum of Prehistory of

Valencia. (Design: Rosa

Bou and Kumi Furió).

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez & Miguel Mezquida Fernández

[page-n-27]

26

Beyond exhumation: Building Memory through Archaeology and Museums

From here, we begin our first incursion into the past so as to contextualize the ideological, political and social reality of the post-war period in which the crimes of the Franco regime took place8, and where

the duality between the victims and perpetrators is clearly defined.

Next, the Municipal Cemetery of Paterna and the Mur del Terrer

are presented together as a unique example of this repression. The

explanation proceeds diachronically, seeing the cemetery as a site of

violence in the past, but also of memory and resistance, and one that

takes on new meaning in the present. The families of the missing persons, the memorialist movement and the local government appear in

this passage through time, as do the technical teams. We then explain

the scientific procedures and multidisciplinarity inherent in the process of the exhumation of mass graves today.

8

With the recovery of the human remains and the objects we go

back once again to the past, in order to remember the people who

were killed and thrown into the graves. This area is the centrepiece

of the exhibition. It is presented as a dialogue between the objects

exhumed and the objects belonging to the families, which, together,

help to reconstruct the socio-political context and the links that were

Event held by the Platform of Associations of

Relatives of Victims at the

mass graves of Paterna

(Photo: Eloy Ariza, Paterna

Municipal Cemetery,

2018).

Our exhibition is limited

to post-war crimes: that

is to say, those committed

after the declaration of

the end of the war on 1

April 1939. The repression lasted until the death

of the dictator in 1975,

when the regime came (at

least officially) to its end.

We should not forget that

violence and repression

can take forms other than

murder, and are manifested in many spheres of

daily life (Rodrigo, 2008).

[page-n-28]

27

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez & Miguel Mezquida Fernández

woven between the prison and the outside world, and between the

inside of the grave and outside. The exhumed materials bear witness

to the precariousness of prison life and to the constant threat of a

violent death, but they also tell us about personal identities and strategies of resistance. For their part, the family objects, accompanied by

the stories of their owners, help us to name and reconstruct the personal and political projects destroyed by the dictatorship. Together,

these objects constitute the elements from which the memory of this

past is built.

The family stories bring us back to the present, to connect with

the final section of the exhibition, which is an open space for individual and collective reflection on the historical events and on how memory is constructed. The journey closes with a final tribute projecting

the names of all the people shot in Paterna between 1939 and 1956.

In addition to the exhibition inside the hall, there is a small display in the museum courtyard, dedicated to the representation of

Franco’s graves in vignette illustrations. This display is designed specifically for the educational visits scheduled by the museum as part of

the exhibition.

Bearing in mind the role of the exhibition and the museum, we

also contacted archaeologists who work in the field of historical memory in different parts of Spain. Queralt Solé, from the Department

of History and Archaeology of the University of Barcelona, explores

in The forgotten bodies of the war the historical contextualization of

violence in the Republican rearguard and the violence of the Rebels

during the Civil War. Establishing the reasons for the deaths and for

the treatment of the dead during and immediately after the war is

essential in order to understand the ways in which human remains

appear in exhumations in Spain. Precisely, Lourdes Herrasti, from

the Anthropology Department of the Aranzadi Science Society in the

Basque Country, focuses on the methodologies and tools of forensic

archaeology in her text The archaeology of memory: the application of forensic archaeology to the graves of the Civil War and the postwar period used to

compile the information needed to restore the identity and memory of

those murdered. Talking about memory and identity inevitably raises the issue of the agency of the families of the disappeared, and also

the need to create spaces to prove that the crimes existed, and to deal

with the trauma. In a study based in Galicia, Xurxo M. Ayán Vila of the

Instituto de História Contemporânea of the Universidade Nova de

Lisboa defends the therapeutic, mnemonic, pedagogical and political

function of community archaeology in his paper This archaeology will be

the tomb of Fascism, or it will be nothing. The role of community archaeology in

uncovering the common graves of Francoism. The voices of Xurxo, Lourdes

[page-n-29]

Beyond exhumation: Building Memory through Archaeology and Museums

28

Handmade pendant

made in prison by Vicente

Roig, shot in Paterna,

for his son. (Photo: Eloy

Ariza, Roig Tortosa family

collection).

and Queralt help to reflect the plurality of ways of thinking and the

cross-sectionality that the archaeological perspective brings to a highly

complex subject of study.

Above we stated that this project has raised multiple challenges.

The most profound of all is, without a doubt, the extremely sensitive

(and chilling) nature of the subject matter and the material culture

that accompanies it. The exhibits, both exhumed and family items,

are sensitive in many ways. Unlike other materials in an archaeological museum, they constitute forensic evidence; due to their state of

preservation, they are particularly fragile; they recall a traumatic past;

above all, they are sensitive because they have an incalculable sentimental value for the families of the victims.

The emotional charge of these objects and stories has deeply

affected the museographic approach to the project. We understand

the museum as a space of negotiation and conflict, where reflection

and dialogue must be encouraged in a multidirectional sense that

abandons the idea of a single truth emanating from the institution.

By immersing oneself in the context, the museum can become a safe

[page-n-30]

29

9

The expression of these

principles in a museum scenario was made

possible by the work

of Rosa Bou and Kumi

Furió, the designers of

the exhibition, who have

scrupulously respected

our wishes and have responded to our concerns

with exquisite professionalism. We would like

to show our gratitude to

them here.

Anthropologists analysing

the piled-up bodies in a

mass grave, prior to the

start of their exhumation.

(Photo: Eloy Ariza ArqueoAntro Scientific Association, Grave 112, Paterna

Municipal Cemetery).

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez & Miguel Mezquida Fernández

space in which to talk about complex issues, conflicts, and controversies. This is why it was so important to gather together different voices from the professional field, the memorialist movement, and the

families. This is also why we wanted to think of the exhibition as an

experiment, testing the potential of museums to approach the memory of the traumatic past in a critical and reflective way (Arnold-de

Simine, 2013).

Based on these approaches, we decided to establish a series of

red lines when conceiving and designing the exhibition9. These

three red lines, with their particular derivations, have ended up constituting a road map that guided us through the entire process.

As a starting point, we were determined to avoid the twin traps of

making the display either excessively spectacular or excessively banal, in the light of the growing media interest in the subject and certain distortions in its treatment (Aguilar Fernández, 2008; Vinyes,

2011; Cadenas Cañón, 2019). The exhibits require a careful scientific contextualization in order to avoid the risk of their fetishization or

even sacralization. It is necessary to balance the need for social and

public dissemination with respect for the items and their owners.

[page-n-31]

Beyond exhumation: Building Memory through Archaeology and Museums

From the very first moment we ruled out the display of human remains (a widespread practice in archaeological exhibitions devoted

to other eras and cultures). Even the use of photographic material is

limited to cases in which the explicit presence of human remains in

the grave was necessary to illustrate the scientific process of exhumation, to bear witness to the systematic practice of mass murder,

or to show the gruesome nature of the graves of Paterna. The aim,

far from being to play down the brutality of a bloody and traumatic

reality, is to guarantee respect for the victims and families, many

of whom are still in the process of mourning. So the bodies of the

victims are not on display, but their presence can be felt through the

objects and their life stories; in the same way, from the outset their

deaths are described as criminal actions. The challenge is to be able

to stir people without upsetting them, to move without being sentimental, to cause a certain unease – based on a profound respect –

without generating overkill.

Secondly, in our story, we have avoided statistics. It is true that

numbers and figures are essential in scientific studies, as they help to

reconstruct the facts with empirical data. They also feature heavily

30

Consuelo Pérez Fenollar

with the photo of her father, Rafael Pérez Fuentes,

shot in Paterna. (Photo:

Eloy Ariza, ArqueoAntro

Scientific Association,

Grave 22, Paterna Municipal Cemetery).

[page-n-32]

31

10

An artistic creation

by Guillem Casasús

Xercavins and Gerard

Mallandrich Miret,

whom we want to thank

for their participation in

this project.

Fragments of a diary,

mounted on the original

document. This is a cartoon by the illustrator Bluff

(Carlos Gómez Carrera,

also shot in Paterna) that

was exhumed in Grave

111 of the Paterna Municipal Cemetery, associated

with Individual 79 (Photo:

Eloy Ariza ArqueoAntro

Scientific Association).

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez & Miguel Mezquida Fernández

in the media and in political discourse, because they are straightforward and easy to understand: so many graves exhumed, so many

people identified. The reality, however, is that focusing on numbers

runs the risk of dehumanizing the story, by making the names and

life stories invisible, and by turning the people shot into a homogeneous mass of victims, into a mere statistic. Above all, we have cited

personal names wherever possible. In fact, one of the meta-narratives of the exhibition is the transition from anonymity to recognition: from the cardboard boxes containing human remains and the

use of scientific terms such as “individual” or “forensic unit”, the

identity of people is gradually defined – through their DNA, their

personal objects, or their family histories – until they can be named.

The exhibition culminates with the memorial Resilience to oblivion10

and with a book where visitors can consult the data available on all

the people shot by the Franco regime in Paterna. This may encourage

families who do not have information about their missing relatives,

or do not know that they existed, to explore further.

Thirdly, the need to humanize the story has also led us to rethink

the way we present the objects. Compared to the standard taxonomy-based displays usually found in archaeological museums, where

the objects usually appear classified as an inventory with identifying

placards focusing on technical aspects, we opted for more organic

compositions and descriptions that place the emphasis on the people

behind the objects. The exhibition’s discursive potential centres on

the objects and their ability to arouse empathy with the stories told,

and so it is vital that the museographical resources support this ambition. This approach, we think, opens up interesting reflections on

the potential of archaeology in the construction of new imaginaries

around historical memory.

[page-n-33]

Beyond exhumation: Building Memory through Archaeology and Museums

Obviously, in addition to the professional challenges referred

to above, any research process entails a whole series of personal and

emotional engagements that are not always reflected in the final result. In this case, however, we feel it necessary to mention them. From

the moment when we took the first steps to define the project until

right now, as we write these final lines, the object of study has moved

us, on a personal level, in a particularly intense way. No one can be

indifferent to the shocking experience of opening a grave containing

a heap of bodies piled up in a totally inhumane manner; or to sharing

in the anxieties, concerns and longings contained in the letters written by those who were in prison, and also of their families suffering

in their homes; or to noting the indefinable smell of the boxes where

the materials that have undergone saponification are stored; or to

holding in your hands a piece of clothing that the family has hidden

in a chest of drawers for so many years – a priceless treasure, the only

material memory of the missing relative; or to listening to the testimonies of people who have experienced in silence the loss of a parent

they never met or who were murdered when they were barely a few

years old; and to those of the new voices of the “post-memory generation” (Hirsch 2015), who, although they did not experience these

events first hand, have inherited the stories and now demand that justice be done.

The work process has been very demanding both personally and

professionally, but it has been exciting as well. It has required a firm

ethical commitment and a rigorous approach. It has not always been

easy to deal with the diversity of viewpoints and, above all, with the

interests that come into play (and clash with each other) when dealing

with such delicate and conflicting issues. Nevertheless, and despite

the dangers of politicization and opportunism, for us the commitment to the families of the victims and to scientific research prevails,

and the conviction that, as an exhibition organized by a public museum institution, The Archaeology of Memory. The mass graves of Paterna

will stimulate reflection on our traumatic recent past and invite us to

think about the scenarios of coexistence that, as a democratic society,

we would like to build for the future.

“I have a few hours left, I will never see you or our children again.

Keep this letter as a memento. Your husband Bautista Vañó.

Goodbye forever”.

32

[page-n-34]

33

Andrea Moreno Martín, Tono Vizcaíno Estevan,

Eloy Ariza Jiménez & Miguel Mezquida Fernández

Bibliography

Aguilar Fernández, P. (2008): Políticas de la memoria y memorias de la política. El caso

español en perspectiva comparada. Alianza Editorial, Madrid.

Arnold-de Simine, S. (2013): Mediating memory in the museum: trauma, empathy,

nostalgia. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke.

Baldó, M. (2021): «Memòria democràtica i política de memòria», en V. Gabarda

(Dir.), Violencia, conceptualización, memoria, represión, estudios, monumentalización, exhumaciones. Valencia 1936-2020, València: 39-58.

Cadenas Cañón, I. (2019): Poética de la ausencia: formas subversivas de la memoria en

la cultura visual contemporánea. Cátedra, Madrid.

Díaz-Ramoneda, E.; Vila, A.; Sancho, S.; Calpe, A.; Iglesias-Bexiga, J.;

Mezquida, M. (2021): «Les fosses de Paterna, testimonis de la maquinària

repressiva del règim franquista al País Valencià», Revista d›Arqueologia de

Ponent, núm. 31, 239-258.

Espinosa, F. (2021): «La investigación de la represión franquista 40 años después (1979-2020)», en V. Gabarda (Dir.), Violencia, conceptualización, memoria, represión, estudios, monumentalización, exhumaciones. Valencia 1936-2020,

València: 91-114.

Gabarda, V. (2020): El cost humà de la repressió al País Valencià (1936-1956). Universitat de València-Servei de Publicacions, València.

García Hernandorena, M.J.; Gadea-Peiró, I. (2021): Etnografia d’una exhumació.

El cas de la fossa 100 del cementeri de Paterna. Diputació de València-Delegació

de Memòria, València.

Hirsch, M. (2015): La generación de la posmemoria: escritura y cultura visual después

del Holocausto. Carpe Noctem, Madrid.

Mezquida, M.; Iglesias, J., Calpe, A., Martínez, A. (2021): «Procesos de investigación, localización, excavación, exhumación e identificación de víctimas de

la Guerra Civil y del Franquismo en el Levante peninsular», en V. Gabarda

(Dir.), Violencia, conceptualización, memoria, represión, estudios, monumentalización, exhumaciones. Valencia 1936-2020, València: 295-314.

Moreno, A.; Mezquida, M., Ariza, E. (2021): «Cuerpos y objetos: la cultura material exhumada de las fosas del franquismo», Saguntum-PLAV, 53: 213 - 235.

Moreno, A.; Mezquida, M.; Schwab, M. E. (2021): «Exhumaciones de fosas comunes en el País Valenciano: 10 años de intervenciones científicas», Ebre 38:

revista internacional de la Guerra Civil, 1936-1939, 11: 125-152.

Moreno, A.; Candela, J.M. (2018): Prietas las filas. Vida quotidiana i franquisme.

Museu Valencià d’Etnologia-Diputació de València, València.

Moreno, J. (2018): El duelo revelado. La vida social de las fotografías familiares de las

víctimas del franquismo. CSIC, Madrid.

Rodrigo, J. (2008): Hasta la raíz: violencia durante la Guerra Civil y la dictadura franquista. Alianza Editorial, Madrid.

Vinyes, R. (2011): Asalto a la memoria. Impunidades y reconciliaciones, símbolos y éticas.

Los Libros del Lince, Barcelona.

[page-n-35]

A model of a sandal carved out of an olive bone

Individual 144, Grave 115. Paterna

ETNO Democratic Memory Collection

Photo: Eloy Ariza-ArqueoAntro Scientific Association

[page-n-36]

35

The archaeology of memory:

the application of forensic

archaeology to the graves of

the Civil War and the postwar

period

Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri

DPTO. ANTROPOLOGÍA, SOCIEDAD DE CIENCIAS ARANZADI

[page-n-37]

The archaeology of memory: the application of forensic archaeology to the graves

of the Civil War and the postwar period

In the mass grave of Priaranza del Bierzo in the province of León, in

the year 2000, a methodological approach combining archaeology

and anthropology was applied in the exhumation and analysis of

clandestine burials of victims of the Spanish Civil War for the very

first time. This intervention by archaeologists and anthropologists

launched a process that has now gone on for more than twenty years,

which has come to be called “the recovery of the historical memory”.

Over this period, the methods used have become more sophisticated,

but at all times the aim has been the recovery of the remains of the

people murdered, in order to record the information necessary to

restore their identity and their memory.

Now that more than twenty years have passed, it is time to take

stock of the process and to examine the contribution of archaeology

to the historical understanding of the repression perpetrated by the

Franco regime.

Nothing tells us more about the horror and injustice of an age

than the sight of human skeletons crowded together in a common grave.

Introduction

Forensic archaeology is heir to the branch of the discipline known

as the “archaeology of death”, from which it has adopted the methods needed to recover skeletal and other remains from individual or

collective burials. Archaeology becomes “forensic” when it focuses

on people who died not of natural causes but by acts of violence, and

provides evidence that can be presented in court or in legal debate.

In the English-speaking world this area of study tends to be

called “forensic anthropology”. The two disciplines are complementary: in archaeology the focus is on the process of recovery of remains

and documentary evidence, while anthropology studies the biological profile of the buried; in turn, legal medicine analyses the cause

of death. When forensic archaeology is applied to the analysis and

recovery of historical memory, it can be termed the “archaeology of

memory”.

The action protocol for the exhumation of victims of the Civil

War and the Dictatorship, dated 26 September 2011, describes it as

an interdisciplinary activity involving historians, archaeologists and

forensic specialists. The latter include anthropologists and forensic

odontologists, as well as specialists in legal medicine.

Archaeological methods unearth remains in mass graves, allowing

them to be collected and then sorted. First, drawings are made of the

positions of the bodies and of the graves themselves, and photographs

36

[page-n-38]

37

Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri

are taken of each individual and of all the features of interest. The results of this exhaustive documentation process are recorded with data

on each individual and the spatial relationships between them, in order to carry out the exhumation in an orderly fashion.

The testimonies of the people who lived through the events or

who heard accounts of what had happened are crucial, because they

provide information about the location of the graves. The same can

be said of the information supplied by witnesses who were children at

the time, and who saw the murders and clandestine burials from their

hiding places. A clear example is the mass grave in Barcones, Soria,

which serves as a model for the discussion of several key aspects.

Recording of testimonies

and information from

relatives at the grave. La

Andaya IV (Burgos).

Importance of the eyewitness offering testimony.

Grave of Barcones (Soria).

[page-n-39]

The archaeology of memory: the application of forensic archaeology to the graves

of the Civil War and the postwar period

38

The procedure for the search, removal and exhumation of human remains is described in the article by Polo-Cerda et al. (2018).

The excavation exposes the skeletal remains by removing the soil

above and around them; using a technique known as the pedestal

method, the remains stand out in relief against the ground. Sometimes it is practical not to preserve the side walls of the grave, because

this makes it easier to access the remains around the entire perimeter, allowing a clearer view of the interior. In trench graves, however,

it is better to preserve the walls in order to highlight the grave’s use as

an improvised burial place.

Exhumation process at

the grave of Barcones

(Soria).

Types of grave

Mass graves are usually rectangular in shape, deriving from the depositing of one or several bodies lying on the ground. In general, the

bodies tend to be laid out in a fairly orderly way adapting to the space

available, regardless of who was in charge of the burial the corpses.

Thus, they might be arranged in alternate head-feet positions, with a

body in each corner, or aligned and overlapping. In the grave in Barcones, Soria, the six bodies were placed very close together, alternating heads and feet.

On other occasions the graves were dug into already existing

ditches, a practice that was much easier and particularly attractive

when the diggers were in a hurry or were frightened. The bodies

would be arranged in lines, sometimes overlapping, sometimes not.

[page-n-40]

39

Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri

Grave of Barcones (Soria).

Arrangement of individuals in the pit.

A clear example of this type is found in Berlanga de Roa (Burgos),

where it is known that a road labourer, who may have known the

victims, buried the five men (among them a father and son); the

bodies overlapped and were arranged with care and respect. In other

cases, a wide ditch was dug that allowed the bodies to be arranged

cross-sectionally, as in La Pedraja (Burgos), where a total of 105 individuals were buried in 10 successive graves; in Fregenal de la Sierra

(Badajoz), with 47 victims in seven graves, and in Villamayor de los

Montes (Burgos), where 45 men were found in two graves. Elsewhere, the bottom of the grave was covered with several bodies and

then others were thrown on top of them. In the graves of Estépar

(Burgos), the bodies of 96 men who had been taken there from Burgos Prison were recovered.

The perpetrators, or the gravediggers, often made use of wells,

mines, and pit caves to get rid of the corpses. There are many examples

in Navarre, Extremadura, and the Balearic and the Canary Islands.

[page-n-41]

The archaeology of memory: the application of forensic archaeology to the graves

of the Civil War and the postwar period

40

The placement of victims

in the pit. Grave of Berlanga de Roa (Burgos).

[page-n-42]

41

Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri

Grave 2 of Estépar

(Burgos).

At the Sima del Raso in Urbasa, Navarre, the corpses of ten people

were thrown into the cave on three different occasions. This suggests

that it was the same people who murdered the victims at the mouth of

the cave then threw them inside.

But the commonest practice was to take the corpses to the cemetery. Bodies found in ditches by the side of the road, if they were not

buried nearby, would be loaded onto pack animals or carts and taken

to the cemetery where the gravedigger himself, perhaps with other

townsfolk, would bury them on the edge of the cemetery, or in the

civil cemetery so as not to contaminate the area where the upstanding

residents of the town were buried.

Many mass graves contain victims of extrajudicial killings in the

cemeteries, deaths that occurred during the first months of the war,

in 1936, but many others hold the remains of people sentenced to

death from 1938 onwards. Cemeteries attached to prisons and concentration camps have also been exhumed: at the prison cemetery of

[page-n-43]

The archaeology of memory: the application of forensic archaeology to the graves

of the Civil War and the postwar period

Valdenoceda, Burgos, a total of 106 corpses of prisoners have been

recovered, and in Castuera, Cáceres, the bodies correspond to people who died or were murdered in the concentration camp. The large

cemetery of La Tahona de Uclés in Cuenca holds more than 570 bodies of combatants from the war hospital and others who died in prison. The frontline hospitals tended to have a space behind the building

that was used as a cemetery for those who died there. Examples in

Catalonia are Soleràs in Lleida, and Pernafeites de Miravet and Mas

de Santa Magdalena in Tarragona, with more than a hundred individuals in each one.

Belongings

The objects that the individuals had with them when they were killed

are often highly personal. The most numerous are items of clothing:

shirt buttons, belts, buckles, loops and trouser fly buttons, and even

zips and garters. Although these are simple, everyday items, they can

be transformed into objects of memory. In one instance in which

the remains of an identified person were handed over to family

members, they were interested in some buttons and the remains of

a buckle that appeared photographed in the report. One of the relatives asked to be able to keep a mother-of-pearl button because “I

am certain that it belonged to my grandfather”. In this way, a simple

button became a relic.

A good example of the variety of the objects recovered is found in

the grave of La Mazorra in Burgos: items of clothing such as berets,

zips and footwear; personal items such as earrings, a comb, a lighter

and a carpenter’s meter, and objects related to health such as a hernia

support and a dental prosthesis.

There are also more specific objects that might once have helped

in the identification of their owner. Objects such as rings, watches

and cufflinks could have been associated with a particular person;

but now, since so many years has passed, these memories have disappeared and the information has been lost.

Sometimes the objects retrieved are personalized. An example is

a silver belt buckle, found in the grave in Bóveda (Álava), belonging to

an indiano (a Spaniard who had made his fortune in Cuba) and which

bore an engraving of the initial of his last name. The historical data

provided strong indications of the man’s identity, which was then

confirmed by genetic tests. Other finds include rings with initials and

the dates of a wedding. In grave 3 at Estépar, for instance, a gold ring

was found bearing two initials, “P and E”, and a date; a member of the

team located a marriage certificate in which the two initials coincided, suggesting that the man in question was a teacher named Plácido

42

Objects recovered from

the grave of La Mazorra

(Burgos). The image

shows that the thirteen

victims in the grave had

their hands tied when

they were murdered and

buried.

The images show the

following objects (and an

injury); clockwise from

top left: woman's cap and

comb, dental prosthesis,

clothes worn, sweater zip,

notch where the projectile

entered the jaw, wick

lighter, reinforcements of

the ends of a carpenter's

measuring instrument,

hernia truss attached to

the left hip, beret, earrings

and shoes.

[page-n-44]

43

Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri

who was married to a woman called Emilia. From the genetic information, it has been possible to identify the group of the other 26 victims who were with him in the grave, all of them murdered on 9 September, 1936, after being taken to the site from the prison in Burgos.

One exceptional find was the discovery of an identification document preserved inside a bottle. In the prison cemetery known as Las

Botellas, where 131 people who died in the San Cristóbal de Ezkaba

prison in Pamplona were interred, each of the victims was buried

with a bottle placed between their legs, containing an official document with the prison’s own letterhead, Ezkaba Sanatorio Penitenciario

de San Cristóbal, which recorded the name of the deceased, their place

of birth, affiliation, offence and the sentence imposed, as well as the

cause of death – usually tuberculosis, an endemic disease in prisons,

especially in one that called itself a sanatorium. This process of documentation complied with the order issued by Franco in January 1937,

ordering the identification of those killed in combat and in prisons.

[page-n-45]

The archaeology of memory: the application of forensic archaeology to the graves

of the Civil War and the postwar period

Biological profiles of the bodies exhumed

The remains of the victims in the graves are collected individually

with their associated belongings, in separate boxes, and are then

transferred to the anthropology laboratory. There, the analyses are

carried out with a standardized methodology for appraisal of the person’s sex, age, possible pathologies, dental features and injuries related to the cause of death.

The vast majority of the victims recovered in the graves of the Civil War are males. It is estimated that fewer than 3% are women.

Almost half of the men were young adults, between 20 and 40

years of age, and around 30% were aged over 40. The third group

were over 50 years of age, and a fourth group aged under 20. However, because of the poor state of preservation a more precise estimation of the age is often impossible, and in these cases the remains are

included under the generic category of adults.

44

Bottle placed between

the tibias. Inside was the

deceased's affiliation

document. Cemetery

of the bottles. Ezkaba.

Pamplona.

[page-n-46]

45

Lourdes Herrasti Erlogorri

Different graves for different types of victim

The graves can be differentiated according to the victims buried

there:

a) Graves containing victims of extrajudicial killings. During the first

months of the war, particularly between the months of July and

November 1936, the period known in Spanish as the “hot terror”,

thousands of extrajudicial killings took place, the product of indiscriminate and uncontrolled violence. This repression was particularly

harsh in the provinces where the coup d’état triumphed and gained

territory as the front line advanced. As the historian Francisco Espinosa emphasizes, these deaths were caused not by the war, but by the

repression. The regions most affected were Castile-León, Galicia,

Navarre, La Rioja and Cáceres.

The victims of this period were the civilian population, men and

women who were arrested for long periods before being taken to

their place of execution. These final journeys were euphemistically

known in Spanish as paseos, or “walks”. The victims were illegally detained, handcuffed, and often killed and buried with their hands tied.

An example is the grave of La Mazorra in Burgos, in which the bodies

of 13 people were buried, two of them women, all with their hands

tied. It is said that the bodies appeared abandoned on the roadside,

because they were seen by passengers on a passing bus. Several local

people collected the bodies and decided to bury them there in a rectangular grave, laid out in a relatively orderly fashion, still with their

hands tied.

Graves of this type constitute the most important and numerous

group. Examples are the cemeteries of El Carmen in Valladolid, with

more than 200 victims; Magallón in Zaragoza with 84, La Carcavilla

in Palencia, with 108; Porreres in Mallorca with 104; La Pedraja in

Villafranca Montes de Oca, Burgos, with 136, and four graves in La

Andaya in Quintanilla de la Mata, Burgos, with 96, and so on.

b) Graves containing victims of “legal” repression. From 1937 the authorities sought to legalize executions through summary trials in which

the sentence was nonetheless a foregone conclusion. These executions were carried out in specific sites such as the walls of the cemetery. The most notorious example is the wall of the Paterna cemetery